Sergio Lombardo, photographed by João Canziani, 2022.

Abstract

Silence is a form of recollection that allows us to let the meanings fluctuate in order to grasp other levels of a manifest plan, free from the constraints of meaning within which we find ourselves entangled.

It is a quiet universe that puts the individual back in touch with “the intuition of the cosmos”.

The feeling of noise has spread above all with the arrival of the industrial society, with the progress of urbanization. Technological progress has gone with the greater acoustic penetration in daily life and “nothing has changed the essence of man as much as the loss of silence” (Picard, 1954).

The following article presents itself as an investigation about the case, going through some of Sergio Lombardo’s artistic productions, identifying the achievement of silence as a common solution.

The first part deals with the origin of this research, with “I Monocromi” (1958-1961), making a first comparison with the musical experiments of John Cage; the second part turns to the Eventualista Theory, created by Lombardo, to reflect with the work

“Sfera con sirena” (1968-1969) on the saturation of the action (noise), through the resolution of the same (silence); the third part shows the transition from physical to mental action with “Progetti di morte per avvelenamento” (1970), deepening the concept of nonsimulation and interiority, towards a new aesthetic landing; the fourth part analyzes the structure of “Concerti aleatori per azioni” (1971-1975) to reflect on the “intransigent” muteness of the technological object; within these different parts, appear extracts from my conversations with Sergio Lombardo that explain his avant-garde thinking on silence.

1. The Monochromes (1958-1961): silence as a synonymous of expressive abstinence

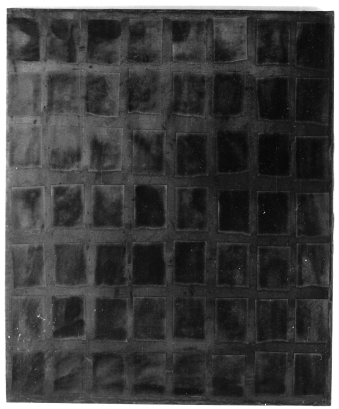

The concept of silence was first experienced by Sergio Lombardo with the creation of the Monochromes, between 1958 and 1961, exhibited in 1962 at the GNAM – Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome1. The artist aimed to produce works that were usable in their materiality, seeking to establish a communication with the spectator, highlighting the pictorial process in its most analytical form; the cancellation of artistic representation in favour of an «expressive abstinence»2, quoting a terminology dear to the author, capable of «stimulating the expression of the contents of ordinary people»3 .

Sergio Lombardo, Black 56, 1960, collage and enamel on canvas, 120 x 100 cm, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo.

Squared or rectangular cards, aligned at a constant distance, serve in I Monocromi di Lombardo as a modular element. The first operation consists in gluing them with Vinavil onto canvas or paper, as dowels of an orthogonal grid, devoid of any external referent. The supports used consist of pre-existing and industrially manufactured materials, and range from sheets to plywood to jute sacks.

The second operation is aimed at applying a single colour. The innovation lies in the fact that at certain points of the surface, the paint thickens to the point of dripping, while some areas are poorly smeared to the point of showing the base, emphasising the manual component.

The canvas, as a porous fabric, assimilates the glassy glue substances of the enamel, creating a contrast between the background, which remains opaque, and the shiny cut-out figure, which returns the absorbed reflective capacity, transforming the grid into a ‘kinetic’ visual field. The chemical reaction that is created destabilises the initially conceived structure and leads to a compositional result, with unformulated and uncontrolled purposes, influenced by the quotient of randomness as the only individuality present.

The importance that the Monochrome can have, from an art-historical point of view, as a pure signifier, according to the logic of ‘degree zero’, is also witnessed by the figure of John Cage (Los Angeles, 1912 – New York, 1992), whose struggles in the field of music characterise the foundations of his thought. The composer states that his interest in the physical and ideal dimension of sound, in the intimate sacredness of silence, was originally triggered by his encounter with the white paintings of Robert Rauschenberg (Port Arthur, 1925 – Captiva, 2008), which he probably saw in New York at the Betty Parsons Gallery. The American artist Irwin Kremen (Chicago, 1925 – Durham, 2020) recalls seeing such paintings by the artist in December 1951, in Cage’s New York flat, before he incorporated them into his Black Mountain in 1952. «What prompted me was the example of Robert Rauschenberg, of his white paintings. When I saw them, I said to myself, ‘Oh yes, I must; otherwise I am late, otherwise music is.»4.

These are five identical canvases, with a few scattered traces of roller, in which, as in Lombardo, Rauschenberg definitively distances himself from his task of expressive authorship

Lombardo summarises this intention in one of our conversations:

In the production of The Monochromes there is only the spectator who looks at the work and does not know what to do, because he sees nothing. The problem lies in the fact that any event, any phenomenon, any complex system, for that matter, if it does not return to its starting point, becomes ‘expressionistic’, especially in the field of painting, of art.

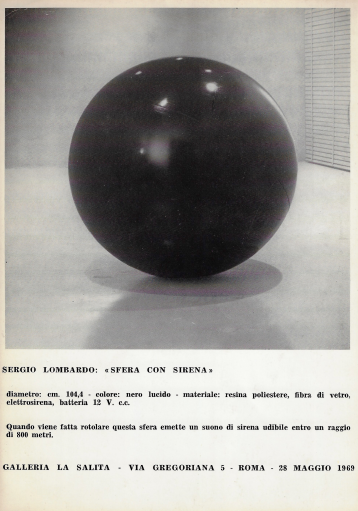

2. Sphere with Mermaid (1968-1969): silence as a resolution of the problem

«Today’s art is not satisfied with simply forming the public and making it act under the direction of the artist; the latter eliminates himself by simultaneously carrying out his own destruction»5, stated Palma Bucarelli (Rome, 1910 – Rome, 1998) in the context of the 1969 Paris Biennale, of which she was curator of the Italian section.

The intention is to give rise to researches that attempt to go beyond traditional painting and sculpture through works that, with different materials and methods, aim to investigate the spatial dimension, analysed by Sergio Lombardo with the formulation of the Eventualist Theory. It includes physical and mental participation on the part of the spectator as the completion of the work that arrives at a new aesthetic result, permitted by experience, from which the author cuts himself off.

The figure of the artist would now seem to coincide with that of the ‘scientist’ who designs functional stimuli, aimed at provoking the action itself: the more heterogeneously a sample of people reacts to the same stimulus, the more they grasp the eventualist purpose.6

Sergio Lombardo in his studio with Seven Spheres with Mermaid, Via dell’Arco di Travertino, Rome, 1970, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo.

The event takes place while the individuality of the viewer manifests itself, as in the case of the problem situations triggered by Sphere with Mermaid, in which the viewer must save his or her own individuality. At that moment one is expressive and not scientific, and I deliberately provoke such an attitude. Everything must return to a ‘detachment’, to a scientific neutrality proper only to the experimenter (Lombardo 2023).

The work Sphere with Mermaid, designed in 1968 and realised in 1969, was exhibited on the occasion of the XXXV Paris Biennale. It consists of a movable sphere with a diameter of 104 cm, made of polyester resin and fibreglass which, when moved from its original position, is capable of producing the deafening sound of an alarm siren audible within a radius of 800 metres. The acoustic signal, located inside and powered by battery, is connected to a mercury switch that is activated in the presence of movement. The alarm ceases only when the art product is returned to its initial position.

The problem arises with the lack of reference points from which orientation can be deduced. The conformation of the work, the circular and hypnotic movement that follows, creates in the viewer a strong sense of ilinx7, vertigo and estrangement, psychologically triggering what the Futurists would call an ‘emergency situation’. The deafening sounds, unconsciously produced, «proliferate by incorporation into the structure of creation, illustrating a greater divergence of cultural codes – acoustic typology – and mundane sources – audience reaction – »8.

The intensity of suggestion increases as the specimen becomes loaded with multiple allusions and meanings. Through traffic and television, many sounds have gradually naturalised and are able to be perceived in everyday life with greater speed. This contrasts with the silence that is intended to be achieved, in Lombardo’s case, only at the moment of resolution.

Sergio Lombardo, Sphere with Siren, Galleria La Salita, Roma, 1969, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo.

The sudden ‘return’ induces greater attention and awareness on the part of the public towards the content of the work with which it interfaces. It is an absence that alludes to the metaphorical self-elimination of the self, as author, (as anticipated in a pictorial sense by The Monochromes) and a lunge against the mass culture of the time, also in an auditory sense. The relationship between the artist and the viewer becomes, therefore, a social issue, through implausible acoustics; an «intimidating scream»9, as Professor Maurizio Calvesi (Rome, 1927 – Rome, 2020) would define it, which does not induce submission, but rather the reaction of the individual towards the artistic product, in an interaction that is at first laboured, then «impossible» with the subsequent production of The Poisons.

«Silence is all sound that we do not understand. It does not exist in an absolute sense, so it may well include sounds and, increasingly, during the 20th century, with the noise of jet planes, sirens, etc.» The way in which he conceptualises worldly sounds10 and their absence is shared and continued by Lombardo himself, who will pay homage to him with the work Sphere with Mermaid, exhibited again in ‘93 at the XLV Venice Biennale, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva11.

The American theorist carries out a reflection akin to the function assumed by Sfera con sirena, both from a social point of view, relating to the new sounds that populate contemporaneity, and from an artistic point of view, since the noise provoked by the above-mentioned work presupposes an investigation into the crystallisation of duration. «We live in the time of noise»12, begins Norwegian writer and explorer Erling Kagge (Oslo, 1963). «Our societies are currently immersed in a widespread desire to saturate space and time, precisely by means of a production of sound without rest»13, points out the sociologist David Le Breton (Le Mans, 1953), to whom he dedicates an essay on the subject.

Silence, in the contemporary world, is intolerable and requires action to reduce its threat. It means introducing a double fear and hostility: the encounter with a world increasingly reduced to signs and noise, less and less inclined to the search for meaning and thought (Le Breton, 2016).

With Lombardo’s Sphere with Mermaid, one arrives at the metaphorical attainment, by trial and error, of an original situation in which the absolute absence of sound dominates. From a visual point of view, the annihilation is suggested by the aseptic place; from an extra-sensory point of view, this work demonstrates the studies carried out by the artist in those years on shamanic techniques, whose contemplation is directed towards an element of surprise that cancels all habitual references. Reason is eluded, the only possible knowledge is ‘superior’, extra-rational. This modification of sensitivity, experienced spontaneously with the occurrence of an unusual event, became, at the end of the 1960s, an object of research for Sergio Lombardo to the point of giving it an artistic form.

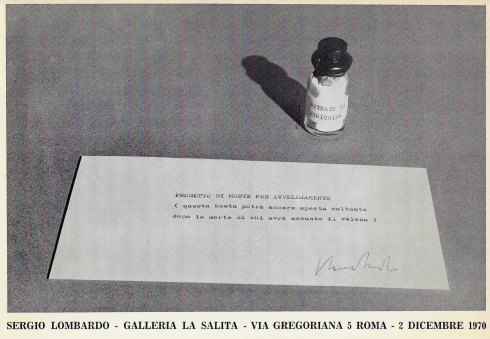

3. Death by Poisoning projects: the silence of non-simulability

Sergio Lombardo comes to an ideological and philosophical crossroads: either life is not an illusion and succeeds in transforming the world, or the only creative moment is death. The artist realised a creation-symbol of this concept, with I Veleni (The Poisons), first exhibited on 2 December 1970 in Rome at Gian Tomaso Liverani’s Galleria La Salita, with no less than 120 pieces, then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and in 1971 also at the Paramedia Gallery in Berlin and at the Christian Stein Gallery in Turin.

The work consists of a small glass vial containing crude nicotine, strychnine or cyanide, randomly chosen by the artist himself, placed next to a sealed envelope with provocative words in the nature of a sentence written on it: Open this envelope after the death of the person who has taken the poison.

The project employs a crude minimalism, in an aesthetic sense, and requires using the quickest mode in the construction of the stimulus, avoiding all the superfluous, including arbitrary choices.

Invitation for the Sergio Lombardo exhibition, Galleria La Salita, Rome, 1970, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo.

In the creation of such a trigger, the author no longer has to work as such, as neither his stylistic identity nor the expression of personal content is required. His role, quoting Lombardo, has become ‘saturated’; an attempt, this, already glimpsed in I Monochromi and La Sfera con sirena, which formulate and declare in advance the structural method of the work, far removed from manuality and inspired creativity. John Cage, like Lombardo, also attempts a reformulation of the role of the artist, through his campaign against ego-investment and concomitant interest in Asian and Christian religious thought.

These considerations have their first socio-cultural impact in the years between 1948 and 1952, with the proposal of his first silent composition, Silent Prayer (1948), and with the realisation of his most famous composition, 4’33’ (1952). The connection between these two different silences led John Cage to develop techniques and rationality, while engaging in the sounds and silences of the world, in order to musically silence society.

In the Death by poisoning projects, the spectator’s victory is not suggested by the action, as in the previous artistic production; not by a consequential logic of cause-effect, but by a complex mental process that triggers psychic movement while remaining motionless, indeed, ‘petrified’. Similar to Cage’s case, the intention in Lombardo is that «another fullness replaces the exuberance in the complex and changing interplay of the environment, that mental sounds rush in to fill the absence of musical sound» (Douglas Kahn, 1997).

Complex in terms of content, The Poisons are able to provoke conflicting reactions, as they display essential elements in a vitrine, alluding to vanitas and transience. As a warning of the ephemerality in existence, the theme of death and the possibility of choosing it voluntarily, as its solemn miniature, is questioned. The emblematic choice between existence and non-existence, between yes to life and annihilation, which is preliminary to all subsequent choices of the individual, becomes constitutive of the work. «Silence allows a heightened sense of existence, embodies a psychic presence that envelops deeply, while remaining intangible» (David Le Breton, 2016).

The power of a poison could, metaphorically, guarantee the sincerity of the experience, excluding all other possibilities: nothing could be more authentic than death, because any other transformation would be nullified.

Death becomes a borderline case of non-simulability, since, for example, the death of the suicide, however consciously premeditated, could never have the character of fiction due to the irreversibility of the event. It is an action that negates the work as a plan of death, the poisonous content of which, if ingested, is sufficient to kill.

It is not an incitement to suicide or murder, for it is clear that the possibility of ending one’s existence by ingesting such poison is more than virtual, since the flask is displayed inside a glass case, promptly controlled by a caretaker.

The interaction, therefore, must involve a strong psychological commitment, it must provoke learning, leaving the playful sphere behind. With this operation, Lombardo subtracts any possibility of a wrong response from the user; he is not, in this case, stimulated, but rather overwhelmed. This is why silence symbolically manifests itself as a reference to death itself and to the game that must take place within the spectator’s psyche. Lombardo shifts the vanishing point of his investigation from manual to cerebral interaction, the latter being more profound and capable of modifying the direct approach to the stimulus. The silent question posed is philosophical, interior, bordering on the spiritual; «the word is voiceless to say the power of an instant, the solemnity of a place» (David Le Breton, 2016).

4. Aleatory concerts for actions (1971-1975): for a silencing project

The Projects for actions are iconographic schemes conceived in 1971 by Sergio Lombardo, through which he realised the Concerti aleatori per azioni, performed for the first time in public in 1972, at the GAP Gallery and Incontri Internazionali d’Arte, in Rome. Then the Teatro Scientifico in Via Sabotino in 1977 and 1980, also together with Cesare Tacchi and Renato Mambor, in whose aleatoric experience they mutually influenced each other. Later, the performances went as far as Tokyo.

Sergio Lombardo, Concert for Dancer, 1973, performed by Anna Homberg, Jartrakor, Rome, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo

Lombardo’s Concerts are logical systems involving all artistic genres: from music to dance, from theatre to poetry, and even painting, engaging dancers, mimes, vocalists, linguists, gymnasts and all manner of artists in schematic tasks that attempt to resolve the genres of traditional art into one general method.

The work of art envisages a split into a first design part, controlled by the author, and a second execution part, repeatable until the concert is resolved.

The projects can be divided into three groups: problem actions, actions with a pre-determined solution (SAS) and actions with statistically self-determining alternative solutions (SAAS). The acoustic index is of three types: variable (in intensity, constant in pitch), modulated (in pitch, constant in intensity), monotonic (constant in both intensity and pitch). The first group relates directly to the previous ones and, as in the ‘problem situations’ encountered with Sphere with Siren, the individual or group of individuals are introduced to a non-ordinary situation. The second group is, on the other hand, based on possible repeated individual choices, through which they attempt to obtain a precise final combination, unknown to them, but previously determined by lot. The result is, therefore, unknown, ‘metaphorically generated by a mind that is as “empty” as it was before it became a mind and, therefore, in tune with the possibility of anything, since no mental image of what will happen has been prepared,’ Lombardo argues, reasoning the silence that shares duration with musical sound.

The third group differs from the second because the final combination, although unknown to the operators, is not predetermined, but is gradually formed during the action, since it is precisely the operators who ‘randomly’ determine a type of solution.

The Stochastic Concerts follow a two-pole scheme: on the one hand the actors, who have to achieve by trial and error (position A, position B and neutral intermediate position) the one behaviour that silences the melody they have involuntarily composed; on the other hand the performers, who read according to a behaviour code and give instructions to an electronic instrument (R-72-SAS or R-73-SAAS) that emits the corresponding sound. The fluctuation in the number of errors committed by the performer is simultaneously translated by the acoustic index that runs through a scale of frequencies: the lower the errors, the higher the errors, and vice versa. Such stochastic music is interested in randomness, a fusion of different elements that, paraphrasing the French philosopher Henri Bergson’s (Paris, 1959 – Boulevard de Beauséjour, 1941) statement on disorder, consists of «a harmony to which we are simply not accustomed». An unintentional sound that goes beyond the boundaries of Western art music and induces listening.

These are unscripted, but randomly created concerts in which a group of people try to solve a problem through an experimental process, by trial and error. They are referred to as modern dances, ‘upside down’ due to the simultaneous composition of motif and choreography, in which the dancers, instead of performing a music or movement they already know, create unknown ones. This logic is defined by Lombardo as ‘athletic’ since it would seem to resemble that of a sports competition in which there is a record within a system of pre-established rules: the athlete, like the actor, can only reduce the execution time by producing a randomly hierarchical order: the order of arrival.

Lombardo points out in a conversation with me:

Think of a statistic related to the field of music. It is clear that it must have a zero mean, so it would be a stochastic trend that comes by chance from somewhere and does not proceed by my taste, but by viable possibilities. It is neutral, then. And it is this neutrality that interests me, so everything ends in silence because it becomes so.

It is a form of non-representational happening that identifies itself in the act of its unfolding, never repeating itself in the same way. It can also be seen as the transformation of the initial negative feedback into a positive one, simultaneously involving the achievement of the goal and the exhaustion of the system. The task is configured as a competition and the aim is to guess «the right facial expressions, the exact phrase to be declaimed, the correct body position to be assumed, generating by intervals an intense neuronal activity»14.

Sergio Lombardo, Concert for Dancer, 1973, performed by Anna Homberg, Jartrakor, Rome, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo

Through such productions, Sergio Lombardo turns to a new conceptual formulation of the interaction between individual and work. The operation of proposing the artistic product to the viewer is overturned in favour of a complete participation in it, for a higher understanding and listening. Such thinking is rooted in a psychological and aesthetic research at the same time, capable of triggering, in a D.Kahn, p. 560. 15 scheme of design and execution, «internal perturbations within the system»16 of the artistic tradition. We are confronted with ontological problems that reflect on eventuality, error and scientificity linked to action, in which the attainment of the condition of silence coincides with the resolution of the triggered question.

At the moment when the spectator achieves silence, he not only reaches the solution of the problem posed by the experimenter, but also experiences a practical pleasure, namely that of ‘doing something well’. The spectator finds himself in a blind alley in which, if he does not solve the problem as he comes out of it, he could get stuck. Beauty manifests itself when you solve the problem, when you achieve a form of operational pleasure (Lombardo, 2023).

Sergio Lombardo with Cesare Tacchi and Renato Mambor, Roma, 1962, courtesy Archivio Sergio Lombardo.

Notes

1 Premio per Giovani Artisti alla Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Roma, 1962.

2 F. Pola, Dai Quadri ai Superquadri, in astinenza espressiva. Intervista a Sergio Lombardo da “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte”, Nuova Serie, n. 32, Anno XLII, 2021, p. 58.

3 “L’artista? Ha l’”astinenza espressiva” (1994), da S. Zacchini (a cura di), Scritti

Volume I 1963-1999, Arezzo, Magonza Editore, 2023, pag. 418.

4 J. Cage, Composition as Process da Il silenzio, Wesleyan University Press, 1958.

5 P. Bucarelli, Italie, dal catalogo Sixième Biennale de Paris. Manifestation biennale et internationale des jeunes artistes du 2 octobre au 2 novembre 1969, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville, Parigi 1969, p. 80.

6 S. Lombardo, L’evento da La teoria eventualista, da “Rivista di Psicologia

dell’Arte”, n.14-15, Anno VIII, 1987, p. 40.

7 R. Caillois, Dalla turbolenza alla regola da I giochi e gli uomini. La maschera e la vertigine [1958], traduzione di L. Guarino, Milano, Bompiani, 2017, p. 62.

8 D. Kahn, John Cage: Silence and Silencing da The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 81, n.

4, 1997, p. 557.

9 M. Calvesi, I “fortuita eventa”, in Sergio Lombardo, a cura di M. Mirolla, catalogo 9

della mostra, MLAC — Museo Laboratorio di Arte Contemporanea, Roma, 1995,

pp. 7-10.

10 J. Cage, Il silenzio [1961], traduzione di G. Carlotti, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2019.

11 John Cage era ancora poco conosciuto nel periodo del Dopoguerra. Era molto particolare quel periodo, ancora la cultura passava attraverso vari canali, tra cui la televisione, e io l’ho conosciuto solo attraverso questo punto di vista, inizialmente.

Lui partecipava in televisione alla trasmissione di Mike Buongiorno, come anche Filiberto Menna. Però poi ho avuto modo di approfondirlo insieme a Lo Savio e a Manzoni. John Cage parlava di innovazione, di Futurismo, studiava la radio futurista e i loro vari programmi, attribuendogli, anche lui come me, una forte radice della cultura e della ricerca. Nel ’93 alla XLV Biennale di Venezia, abbiamo fatto un omaggio a John Cage e la critica che organizzò l’esposizione era Alanna Heiss del PS1 (Public School One) di New York. Io avevo portato la Sfera con Sirena (1968-1969), i Concerti Aleatori (1971-1975) e le mattonelle stocastiche che formavano il Pavimento Stocastico (1993); è proprio in questa mostra, in omaggio a John Cage, che presentai i miei primi pavimenti stocastici. Conversazione con Sergio Lombardo (novembre 2020).

12 E. Kagg Il silenzio [2016], traduzione di M. T. Cattaneo, Torino, Giulio Einaudi, 2017.

13 D. Le Breton, La sovranità del silenzio, traduzione di E. Mancino, Milano, Mimesis, 2016.

14 S. Lombardo, Progetti per azioni, 1971-1975, da Metodo e Stile. Sui fondamenti di un’Arte Aleatoria Attiva in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 3, Anno II, Roma, 1980, p. 94.

15 D.Kahn, p. 560.

16 M. Mirolla, Underground Eventualista. La ricerca estetica in Italia 1972-2019, da “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte”, Nuova Serie, Anno XXXIX, nº 29, 2018, p. 28.

Bibliografia

AA. VV., Danger Art, in “Flash Art International”, 1978.

H. Bergson, La filosofia dell’intuizione [1919], Volume 8 di Cultura dell’anima, traduzione di G. Papini, Lanciano, Carabba, 2008.

P. Bucarelli, Sixième Biennale de Paris. Manifestation biennale et internationale des jeunes artistes du 2 octobre au 2 novembre 1969, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1969.

J. Cage, Il silenzio [1961], traduzione di G. Carlotti, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2019.

J. Cage, Composition as Process, da Il silenzio, Wesleyan University Press, 1958.

R. Caillois, Dalla turbolenza alla regola da I giochi e gli uomini. La maschera e la vertigine [1958], traduzione di L. Guarino, Milano, Bompiani, 2017.

M. Calvesi, I “fortuita eventa”, in Sergio Lombardo, a cura di M. Mirolla, catalogo della mostra, MLAC — Museo Laboratorio di Arte Contemporanea, Roma, 1995.

A. Camus, Noces, Paris, Gallimard, 1959.

P. Ferraris, Psicologia e Arte dell’evento. Storia eventualista 1977-2003, Roma, Gangemi, 2004.

A, Homberg, Opera fissa, forma mobile e progetto indeterminato, da Arte Aleatoria: osservazioni sulla storia del metodo casuale, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” nn. 6/7, Anno IV, Roma, 1982.

E. Kagge, Il silenzio [2016], traduzione di M. T. Cattaneo, Torino, Giulio Einaudi, 2017.

D. Kahn, The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 81, n. 4, 1997.

D. Le Breton, La sovranità del silenzio [2016], traduzione di E. Mancino, Milano, Mimesis, 2016.

S. Lombardo, Progetti di Morte per Avvelenamento, Macerata, Artestudio, 1971.

S. Lombardo, Elusione della ragione e “situazioni d’emergenza”, da Immagini indotte in stato di trance ipnotica, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 1, Anno I, Roma, 1979. S. Lombardo, Il superamento della “finzione”, da Immagini indotte in stato di trance ipnotica, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 1, Anno I, Roma, 1979.

S. Lombardo, Autenticità e irripetibilità dell’esperienza estetica, da Metodo e Stile. Sui fondamenti di un’Arte Aleatoria Attiva, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 3, Anno II, Roma, 1980.

S. Lombardo, Progetti per azioni, 1971-1975, da Metodo e Stile. Sui fondamenti di un’Arte Aleatoria Attiva in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 3, Anno II, Roma, 1980.

S, Lombardo, La simulazione della spontaneità, da Sulla Spontaneità, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” nn. 6/7, Anno IV, Roma, 1983. S. Lombardo, L’evento, da La teoria eventualista, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’’Arte” nn. 14/15, Anno VIII, Roma, 1987.

S. Lombardo, Eventi, 1968-‘79, in Guardare Attivamente, Catalogo della mostra, Napoli, Jartrakor – Studio Morra, 1988.

S. Lombardo, L’Avanguardia difficile, Roma, Lithos, 2004.

S. Lombardo, Sfera con Sirena, 1968-69 in Sergio Lombardo. 12×12” mappe di Heawood, Firenze, Vallecchi, 2004.

S. Lombardo, Monocromi (1958-1961), Milano, Silvana Editoriale, 2018.

M. Mirolla, Underground Eventualista. La ricerca estetica in Italia 1972-2019, da “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte”, Nuova Serie, Anno XXXIX, n. 29, 2018.

D. Nardone, Dai Monocromi ai Gesti Tipici (1959-1964), Catalogo della mostra, Roma, Studio Soligo, 2002.

A. B. Oliva, La Biennale di Venezia. XVL Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte. Punti cardiali dell’arte, Padova, Marsilio, 1993.

M. Picard, Le monde du silence, Paris, PUF, 1953.

F. Pola, Dai Quadri ai Superquadri, in astinenza espressiva. Intervista a Sergio Lombardo da “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte”, Nuova Serie, n. 32, Anno XLII, Roma, 2021.

P. Weibel, E. Gillen, 1968: The End of Utopia?, in Art in Europe 1945-1968: Facing the Future, Tielt, Lannoo, 2016.

S. Zacchini, Le scelte coraggiose non passano inosservate, da “Le courage des positions extrêmes”: Palma Bucarelli e l’avanguardia romana alla Biennale di Parigi del 1969, in “Rivista di Psicologia dell’Arte” n. 29, Nuova Serie, Roma, 2019.

S. Zacchini (a cura di), Scritti Volume I 1963-1999, Arezzo, Magonza Editore, 2023.